By Ketil Moland Olsen, Senior Project Manager at Media City Bergen

Media City Bergen is a Media Innovation Cluster based in Norway. This spring, we were admitted into the 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges. We spent the next six months experimenting our way to next-generation AI-assisted storytelling with renowned newsrooms such as The Guardian, Deutsche Welle, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Science Media Center Germany, and Sveriges Radio.

As a Media Innovation Cluster, Media City Bergen is a bit different from our collab peers. We have been a collab within the collab, with four separate member organisations participating under the Media City Bergen umbrella. The organisations are the financial newspaper Dagens Næringsliv, the regional newspapers Fædrelandsvennen and Stavanger Aftenblad, and the AI-based-fact-checking-company Factiverse. It was the first time a consortium of organisations participated in the collab Challenges, which made us even more excited about the journey ahead.How might we use modular journalism and AI to assemble new storytelling formats?

Our challenge was this: The team will explore opportunities to tell journalistic stories in different ways to different people in different contexts. A specific focus will be on developing new storytelling formats to reach currently underserved audiences. How might we use modular journalism and AI to assemble new storytelling formats?

Phrased differently: How can we structure our journalism in smaller pieces that can be stitched together in different ways at individual lengths to serve several target audiences in ways that better resonate with them than current journalism does?

It’s a pretty broad scope, so our first step was all about narrowing the focus. The skilled organisers at Polis – the journalism think-tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science and mentors from Clwstwr and BBC News Labs led us through a design thinking process. We looked for so-called underserved audiences – readers, watchers, and listeners that are not currently served satisfactorily by news media. There are numerous underserved audience groups out there. We decided to focus on young readers – specifically those between 18 to 24 (Generation Z) and 25 to 35 years old (Generation Y aka Millennials). These segments are typically less engaged by traditional news stories than older audiences, so most news organisations work hard on finding better ways to serve them.

From our first physical team meeting in Arendal in August 2021. From left to right: Ketil Moland Olsen (Media City Bergen), Frode Nordbø (Fædrelandsvennen), Gaute Kokkvold (Factiverse), and Mailinn Mersland (Fædrelandsvennen).

Understanding the Audience Challenge

So what’s the problem? Why are these consumers not engaged? Let’s start with the typical way young readers currently consume news. As stated in a recent Reuters Institute report:

While those over 35 are likely to first go directly to a news site via an app or the mobile browser (39%), Gen Z are more likely to turn to social media and messaging apps (57%). In other words, news brands are less important for this group than for over 35s. Gen Y are somewhere in the middle, with 43% getting their news via social media and messaging apps and 33% directly.

Younger readers rely more heavily on social media to update themselves, which poses a challenge – not only for the news organisations but potentially also for the sustainability of our modern democracy. Social media is typically tailored to the reader’s tastes and does not necessarily provide a balanced view of reality.

What does this mean for the news brands? The Reuters Institute report continues:

Insights from our digital tracking of news users’ mobile consumption reiterate that news brands play a very small role in young people’s lives. Most smartphone time was taken up by social network apps, internet browsers, podcasts, mail, and movie/music streaming devices – followed by dating apps, maps, and transport applications. Young people have a very low threshold for apps that don’t provide a great experience, while they value services that are relevant and useful at all times. No news app was within the top 25 apps used by all the respondents in the study, whereas Instagram was the application found on almost all phones with the highest use in terms of daily minutes used.

There is some consolation to be found in the report:

This does not mean that traditional brands are not valued by young consumers. Most do have an ‘anchor news brand’ that they will turn to when a major story breaks and needs verifying – in our qualitative research study this was typically the BBC or Guardian in the UK, and CNN or the New York Times in the US. The choice of this brand is often heavily influenced by early parental influence but the format is almost always digital.

To conclude on a positive note, there seems to be a potential for reaching the younger generations directly, but we need to do some heavy lifting to find out what works for them.

Using younger subjects and sources in the storytelling might efficiently increase content consumption in the younger target group.

Now we had our target group. The next step was analysing market data collected by newsrooms in our team. Aggregated qualitative and quantitative data suggested that young people are interested in much of the same as older readers. Part of the challenge, it turns out, is related to the persons in the news stories. At least for some of our newsrooms, the subjects and sources in their reporting are typically substantially older than the target group they are struggling to reach. According to the analysis, using younger subjects and sources in the storytelling might efficiently increase content consumption in the younger target group.

Furthermore, surveys and interviews from our newsrooms’ internal research indicate that young people want to learn more from journalism. As an experiment, one of our participating news organisations attempted to emphasise learning points and distilled critical takeaways in the text. The goal was to help the readers understand what knowledge they should get by reading the article. And judging from the feedback after the experiment, highlighting the learning points and takeaways seems to be a way to increase both reading and comprehension among the young.

An interesting paradox surfaced during the discussions in our research phase. We know that editors continuously optimise the angling of stories and the content mix of front pages for the average consumer persona. It increases the readership, but it also optimises content for the average reader – who typically belongs to the older reader group.

What happens, then, when we publish an article that targets young audiences specifically and doesn’t engage older readers at all? We get low figures and low visibility on the front page – even though this story might effectively engage the younger readers we are trying so hard to reach. We can solve some of this problem with personalisation, but that comes with its own set of challenges that we need to mitigate.

Moreover, the group’s internal testing, paired with external research, indicates that the format of the content plays a significant role when young people want to update themselves on the news. And here, the importance of written text cannot be overstated. In addition, a combination of sound, image, and text customised for mobile platforms seems to work well. As this happens to be the format of Instagram and Snapchat, this is hardly surprising.

The Micro Fact Box is Born

Let’s take a moment to sum up our journey so far. We have identified an underserved group – the young consumers – and we have learned quite a bit about why they are currently underserved. Our next step: To find ways of better serving them. And as the very name of the 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges suggest: AI should be part of the mix.

Anyone involved in product development knows that it’s all about creating solutions that solve problems rather than creating solutions that look for problems. And this is surprisingly hard. For starters, it’s relatively straightforward to dream up disruptive and potentially world-changing solutions for future generations – which would also require massive changes in the established journalistic workflows. On the other hand, it’s easy to fall into the trap of over-engineering the experience for the consumer. Do they want to lean back, lean forward? That depends on the context. And then, it’s the countless other variables we need to take into account. Striking a balance is challenging.

One of the team’s early ideas proposed changing the way we write stories from the bottom up. Journalists would enter tiny atoms of information enriched with metadata into a specialised CMS and then feed the resulting data structures into a machine learning algorithm that would stitch the story together in a custom-tailored way for a specific consumer in the receiving end. As our group’s research indicates, young people want less text and more visuals. The suggested approach could certainly be a step in this direction, customising content to the receiving end without manually carving out several versions of the same story. Given that we only had a couple of months to make our vision a reality (the collab had a deadline in November), we quickly realised that this idea was out of scope for now and continued boiling down the core idea. Still, ideas from this phase were beneficial, and fragments have found their way to our current prototype. (Our collab peers Deutsche Welle, Il Sole 24 Ore, Maharat Foundation, and Clwstwr created a related concept. You can check out their idea at their project website.)

We continued tinkering with both the problem and our brainstormed solution ideas, simplifying in both ends as we progressed. And as it turned out, sometimes exciting innovation comes in increments rather than in the giant leaps of significant disruptions. Early this fall, we had boiled the idea down to an essence we could work with and a proposed solution that we could realistically build and test during the given timeframe.

Our problem assumption: News journalism often takes core concepts for granted. Young news consumers often lack knowledge about these concepts. Hence, the lacking knowledge becomes a barrier to entry for the given consumers.

Our solution idea: By highlighting words and concepts we assume to be difficult and correspondingly embedding small explanatory fact boxes in the text, we might bridge the core concepts knowledge gap for consumers who need it.

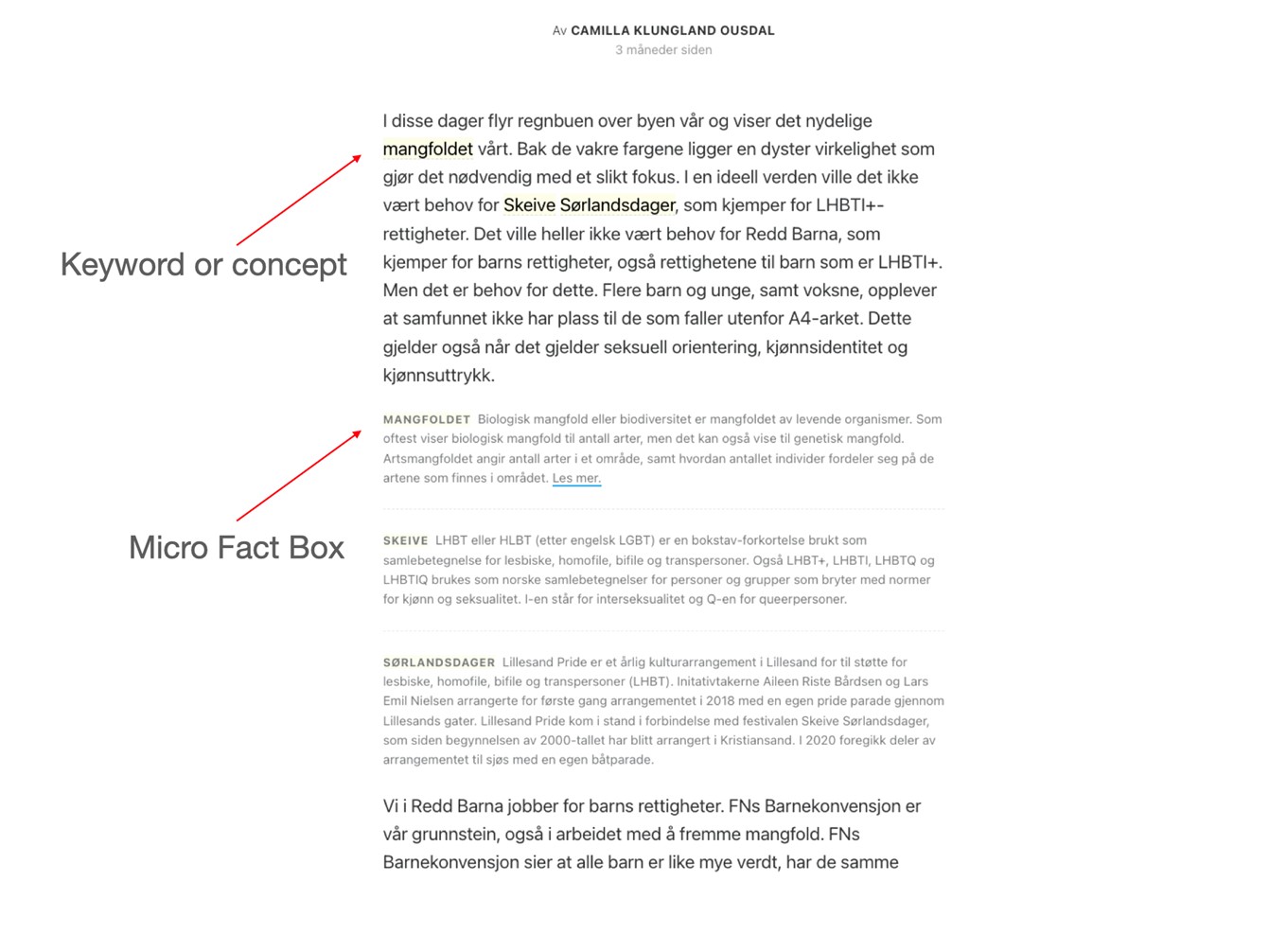

We hypothesised that we could enrich existing journalism with extra information by using simple fact boxes and named our idea Micro Fact Box. Nice name, but would it survive the initial contact with users?

We hypothesised that we could enrich existing journalism with extra information by using simple fact boxes and named our idea Micro Fact Box. Nice name, but would it survive the initial contact with users?

To find out, we set out to build a prototype. Luckily, we had several talented developers on the team. One of them, Frode Nordbø from Fædrelandsvennen, conjured up a working demo just hours after we nailed the initial idea. He even wrote a simple algorithm that ranked all the words in the Norwegian language from most to least used – as an early way of finding words to highlight. We could now run text articles through Frode’s algorithm, and it would automatically tag the most difficult words – in this case, least used words in the Norwegian language – for us. Some of the words were somewhat surprising and out of context, but we decided it would be sufficient to prove our concept.

Next, users should be able to click on the highlighted words to see their definitions. Instead of implementing the classical pop-up box, familiar from Wikipedia, Frode made a promising twist. He designed an in-line fact box that, when clicked, appeared between two paragraphs in the article. We now had the words, and we had the micro fact boxes. But where to find the content for the fact box? For the prototype, we decided to pull the definitions straight from Wikipedia.

Our initial Micro Fact Box prototype. Fact boxes between the paragraphs expand into visibility when the user clicks on a highlighted keyword or phrase in the text.

Field Testing Our Assumptions

While we were busy developing our prototype, we realised that our proposed solution rested on a slightly flaky foundation of assumptions. We needed to test more with real consumers from the right target groups. So while Frode continued working on the prototype, other team members worked on user research. We attempted to tackle the most critical assumption head first: Do young readers lack knowledge about core concepts in news articles?

To find out, Dagens Næringsliv conducted a low-tech experiment for us. They sampled three articles from their publication, printed them, and handed the copies out to a panel of young subscribers. Then, they asked the participants to read the articles with pen in hand, highlighting any difficult words or concepts they came across. We were surprised by the results. Almost none of the participants had highlighted any words or concepts at all. One of the articles had a few highlighted words, but the persons who had made highlights commented that a sufficient explanation came later in the text.

If we were to do this test again, we would probably quiz the readers about comprehension rather than ask them.

Had we headed straight down the wrong track? Strictly speaking, we could have taken these results as verified proof that we were solving the wrong problem with our Micro Fact Box concept. However, we realised that we might have been asking inappropriate questions – or rather asking questions to the wrong persons. The test panel participants were all subscribers of Dagens Næringsliv, and – as paying customers – we would expect them to find the publication’s content within reach. On the other hand, it’s likely that they were not representative of the average person in Generation Y or Z. This turned out to be one of several essential learning points for us. If we were to do this test again, we would probably quiz the readers about comprehension rather than ask them.

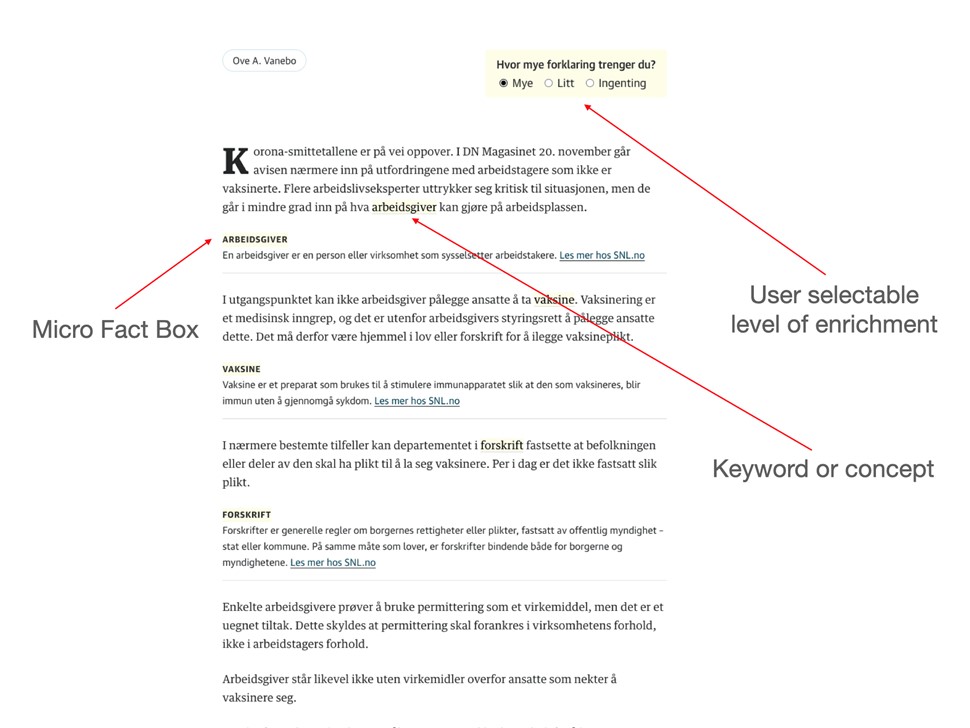

Meanwhile, designer and frontend developer Alexander Prestmo from Dagens Næringsliv joined forces with Frode on the project. He implemented the original idea with DN’s look and feel and added some excellent new features, such as a user-selectable amount of keyword extraction.

Now, we were ready to do the first real-world user test of the prototype. We recruited a handful of students between 20 and 29 years old, invited them to Dagens Næringsliv’s offices, and let them do an unsupervised test drive of our solution. It was a bit of a nerve-wracking experience, but that feeling quickly changed to relief when we realised that the test pilots intuitively understood our Micro Fact Box concept. Indeed, some wrinkles needed ironing, but the tests increased our belief that we were onto something. Here are some of the comments we gathered from the test participants:

I think this feature is useful when reading articles with complicated words.

It’s beneficial if you are a non-native speaker of the language.

It might force me to read more of the text.

It should focus on the “hard words”.

You should state why you highlight certain words.

It was motivating to receive this feedback, but there are still a lot of questions to answer. The natural next step would be to test the concept quantitatively with a larger sample of news consumers. We couldn’t do this in time for the collab deadline, but don’t be surprised if you see Micro Fact Boxes appearing in your favourite online publication soon.

Eager to test the prototype? You'll find it here.

A young user is testing our prototype in Dagens Næringsliv's offices. Gaute Kokkvold from Factiverse is observing.

Highlighting the Right Words

No JournalismAI Collab Challenges without AI as part of the solution. And this is where Media City Bergen-member Factiverse and their representatives Maria Amelie and Gaute Kokkvold comes into the picture. Factiverse is an organisation that develops tools that automate research and detection of misinformation with cutting-edge AI and Natural Language Processing. They have developed the machine learning engine and APIs during the collab that will extract the challenging words and concepts in news articles. The engine will also lookup keywords and concept definitions from third-party sources such as Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias. It’s still in the early stages of development, but the engine can already distinguish between people, places and organisations. Furthermore, Factiverse is developing a journalist-facing frontend, where the highlighted words can be verified and modified. The plan is to integrate this frontend with different newsroom CMSes.

Highlighting the right words for the right readers at the right time is one of the significant challenges ahead of us.

Highlighting the right words for the right readers at the right time is one of the significant challenges ahead of us. Personalisation seems like an inevitable component here, and feedback from readers (through tracking what micro fact boxes are opened and not opened) can be an efficient way of training the machine learning algorithm that decides what keywords to highlight. We are looking forward to getting to this stage of the project.

As we write this, the project’s developers are busily connecting the solution’s front-end and back-end components. When the pieces are puzzled together, we will be able to test the complete, automated workflow. We are optimistic that the experiments conducted during the 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges will make it into the newsrooms’ product in one way or another.

We hope that our Collab experiment is the first of several steps to explain the news in a way that works for young audiences.

Crunch time multitasking in Oslo. While participating in the biweekly collab status meeting, Gaute Kokkvold (Factiverse) and Alexander Prestmo (Dagens Næringsliv) make some adjustments to the prototype.

Takeaways and the Road Ahead

When innovating in the intersection between journalism and cutting edge technology, it’s easy to think too big too fast. While working on the Micro Fact Box project, we have seen a lot of possibilities for expanding the concept. "Why don’t we create a CMS for fact boxes where we can manage the text and stitch the boxes together as full-blown timelines? And while we are at it, why don’t we develop a machine learning algorithm that writes the text in the fact boxes for us and creates customised versions for the various target groups?”

These might all be great ideas, but we need to learn to walk before we can run. By validating the puzzle pieces individually, it’s more straightforward and less risky to expand the core concept. AI will likely be an extensively more significant part of the mix as we keep developing the idea. Machine learning is already identifying the key passages of the articles and will do so increasingly more precise as we train the algorithm. Later on, machine learning might also be writing or adapting the text we display in the fact boxes.

When used optimally, machine learning might enhance journalism significantly. But it’s not a magic bullet. And no, bots will not take over the journalistic profession anytime soon and make us humans redundant. We can, however, expect them to be increasingly well-functioning “colleagues” shortly—colleagues without a sense of humour and cultural knowledge. The most significant potential of AI in journalism is likely to be found in the intersection between humans and machines. Together, we might just change the world – a tiny bit at a time.

But it always starts with the users (in this case, both journalists and consumers) and their needs. Let’s not forget that.

Our most current version of the concept at the time of publishing. Note the new feature that lets users select their desired amount of fact box enrichment.

Acknowledgements

The 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges has been a unique experience. For the Media City Bergen team, it’s been about learning to collaborate as a group (the Media City Bergen participants) within the group (the EMEA collab team) within the group (the global collab team) – a Matryoshka doll of different layers, in other words. We have tried, failed and learned together, but the most exciting part has been learning together as an international ecosystem. It’s been inspiring to see what the other teams have created. At the same time, it’s interesting to realise that all of us face many of the same challenges independently of differing cultures and our physical locations in the world.

We would like to take this opportunity to thank all our 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges peers. It’s been inspiring to learn from the global community. Midway through the project, we found common ground with Bayerischer Rundfunk and Science Media Center Germany, who worked on a project with similarities to ours. We want to thank you kindly for a friendly and fruitful exchange of ideas, problems, and solutions. A special thanks go to Marco Lehner, Cécile Schneider, Rebecca Ciesielski from BR, and Meik Bittkowski from Science Media Center Germany. Make sure to check out their project website.

From our own teams, we want to thank Anders Hamre Kulien and Siri Andresen from Fædrelandsvennen, Frode Buanes, Julie Lundgren and Petter Winther from Dagens Næringsliv, Lars Helle and Elin Stueland from Stavanger Aftenblad, and Marianne Fjellhaug and Charlotte Vindenæs from Media City Bergen for great behind the scenes-work.

Finally, a big thank you goes to the collab organisers: Mattia Peretti and his team at Polis – the journalism think-tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and our mentors Shirish Kulkarni from Cardiff Clwstwr and David Caswell and Jane Birch from the BBC. We are grateful for the opportunity and hope to be collaborating with you all again in the future.

The Micro Fact Box Team: Frode Nordbø (Fædrelandsvennen), Mailinn Mersland (Fædrelandsvennen), Rolf Frøyland (Stavanger Aftenblad), Maria Amelie (Factiverse), Gaute Kokkvold (Factiverse), Ingeborg Volan (Dagens Næringsliv), Alexander Prestmo (Dagens Næringsliv), Anne Jacobsen (Media City Bergen), and Ketil Moland Olsen (Media City Bergen).

We presented our work at the JournalismAI Festival. You can watch it below.

Other projects from the 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges

That’s all, folks! But before you go, make sure to check out the publications and websites of our collab peers. It’s a massive amount of hard-earned lessons to be learned in there, and you can have it all for free:

The Guardian: Talking sense: using machine learning to understand quotes.

Deutsche Welle, Il Sole 24 Ore, Maharat Foundation, and Clwstwr: Modular Journalism.

Sveriges Radio: Project makes podcasts and on-demand radio more accessible.

SMC and BR AI: Science in Context: Generating Fact Boxes with AI.

Tamedia/TX Group: Automatic Storyline Detection to Better Serve our Audience

This project is part of the 2021 JournalismAI Collab Challenges, a global initiative that brings together media organizations to explore innovative solutions to improve journalism via the use of AI technologies.

It was developed as part of the EMEA cohort of the Collab Challenges that focused on “How might we use modular journalism and AI to assemble new storytelling formats and reach currently underserved audiences?” with the support of BBC News Labs and Clwstwr.

JournalismAI is a project of Polis – the journalism think-tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science – and it’s sponsored by the Google News Initiative. If you want to know more about the Collab Challenges and other JournalismAI activities, sign up for the newsletter or get in touch with the team via [email protected].